In last week’s article I wrote about the importance of network building for creative practitioners and touched on one aspect that I felt makes it perhaps the most beneficial component of any artist’s practice. This week I’d like to tease out that point and elaborate on something I think most persons feel uncomfortable speaking openly about, that is, the true cost of creativity. At this point, you might be tempted to think I’m referring to the financial cost but the cost I want to focus on now is far less tangible. It’s the kind that could never really be paid off in a lifetime as a practicing artist.

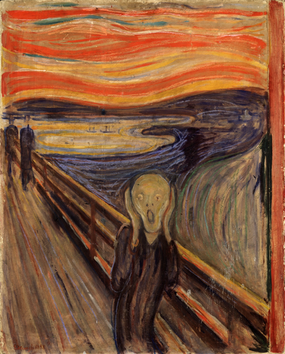

The idea of the tortured artist is inescapable. For centuries we’ve been conditioned to believe that artists must suffer for their art. We’re told, “That’s why it’s called pain-ting.” We believe that creativity is fuelled by the demons wrestled in our darkest hours. And because that pain has been romanticised for so many years we believe that it is absolutely necessary in order to make “great art.” But how much of that pain is a naturally occurring part of the human experience and how much of it is the result of man-made conditions designed to prevent creative practitioners from realising their full potential?

Throughout art history, artists have always been associated with depression or some sort of compromised mental health. In fact, endless studies have been conducted in an attempt to determine whether or not creative individuals are more inclined to be affected by these. One such study was done in 2015 when Kari Stefansson, founder and CEO of deCODE, along with a group of scientists in Iceland reported that persons in creative disciplines are 25% more likely to have genetic variants that raise the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as opposed to persons in less creative fields. An earlier study led by Simon Kyaga at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute where they tracked nearly 1.2 million Swedes working in creative fields revealed even more troubling statistics: writers were 121% more likely to suffer from bipolar disorder, and nearly 50% more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

So what does all of that mean? While I don’t necessarily subscribe to the idea that there’s any particular inherent gene that puts artists more at risk, I do believe that wildly fluctuating living and working conditions create the perfect breeding ground for symptoms of depression to manifest. And for others, those fluctuations can worsen existing mental illnesses. Therefore, on the surface level, one might be tempted to make the assumption that the vast majority of creative individuals are distressed simply because that is their nature. However, a closer look at the overlapping root causes would prove otherwise. But before I get to the root causes I’d like to take a closer look at how this link between creativity and depression came about.

Most mental health professionals would agree that depression is amplified in those persons who spend a lot of time ruminating on their thoughts. And since creative practitioners spend a significant portion of their practice doing just that, it makes sense that they would be most at risk for depression and other related illnesses. But why do artists spend so much time replaying painful experiences? Aside from the fact that society has convinced them that the process of creation is a painful one that must be endured for the sake of “great art,” artists are essentially problem solvers. They spend a lot of time thinking about what happened, what could have been done differently and how the choices made could affect the rest of their lives, all in an attempt to figure things out. Most times this results in a wide range of feelings including doubt, inadequacy, frustration and in worst-case scenarios, self-hatred.

The culture of art production (in my opinion) has always advocated the exploitation of depression and mental illness. The idea that artists should continuously re-hash painful experiences in the hopes of creating something great that could potentially launch their career is a formula still being touted in some parts of the world as “the best way to go.” But is it? Some artists have refused professional help for fear of losing their “genius,” while others have engaged in destructive behaviour in order to induce and prolong feelings of despair. Now, of course, no one can dictate how artists should deal with their pain. Their methods for recovery should be something they determine for themselves, without being swayed by persons looking to capitalise on said pain. Whether they find relief after channeling their experiences into works of art or in another area altogether, it should be recognised that there is no rule that says all artists must continue to suffer until the very end. It should be emphasised that great art can be made without compromising one’s mental health. In the same way, one can receive medical treatment if an illness is present and continue to make great art.

Ideally, any period of depression should be used as an opportunity to focus on the areas that need changing in order to improve one’s quality of life. It is common knowledge that the creative industry is a high-stress environment that offers minimal job security, zero guarantees and very little benefits. Knowing this, it is crucial that you build a strong network of peers that will rally around you in your time of need, and for everyone else (friends of artists, relatives, patrons etc). I urge you to examine your own complicity in the idea of the tortured artist. By perpetuating this idea (whether knowingly or unknowingly) you ignore the very real ways societies fail their artists, which more often than not, are the main reasons artists experience depression in the first place.

So how can you tell if what you’re experiencing is just a passing mood or perhaps something more serious? I would say that if you can’t tell the difference then you should probably contact a mental health professional.